More about art, technology, and experience

Sunday, March 22, 2015 at 1:45AM

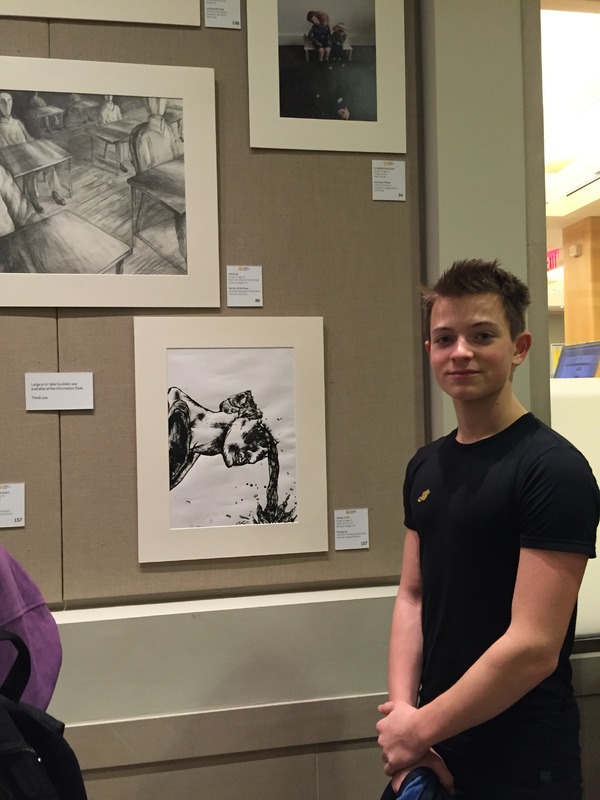

Sunday, March 22, 2015 at 1:45AM Last night (most of) my family attended the reception for the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards. What’s cool is that this program has been around since the ‘20s and claims some startling alumni like Andy Warhol, Sylvia Plath, Truman Capote, Richard Avedon, Robert Redford, and Joyce Carol Oates (and many others at this level — it’s funny to think of these artists submitting for teen awards).

Of course I was proud to honor my son (drawing) and my daughter (writing, couldn’t make the reception). Walking through the exhibition, I was struck by how conventional the works were (albeit very impressive). Painting, drawing, photography. A few photos of sculptures. I feel I’ve been waiting for years for the art world (broadly conceived, not just the Art World) to catch up, technologywise, with the rest of civilization. When photography as art began to emerge — 100 years ago! — it seemed to spell the end of representational painting. I believe strongly that technology drives transformations in artistic production (see also my posting on Tim’s Vermeer), and it follows that the art that tells us the most about the world today (wherever) must take place in the context of today’s technology. (This is not at all because technology itself is the only story — in short, it’s because technology is always intertwined with language/culture and economy in the broad sense, much has been said, and will be said, on this).

You might think, well, these are kids in school. They are learning the basics. But two weeks ago, my son and I navigated a few art fairs here in NYC (Armory, Scope, and Volta).

We had a blast and saw some good work, but again, I was surprised at how much traditional painting, drawing, photography, and sculpture we saw. The topics were often up-to-the-minute (police brutality was a recurring theme), but the media themselves were quite familiar.

The obvious argument here is that these are art fairs — commercial affairs — and readily acquirable and hangable art forms are the most appropriate media here. And ditto for commercial galleries, which the fairs are mirroring.

The obvious argument here is that these are art fairs — commercial affairs — and readily acquirable and hangable art forms are the most appropriate media here. And ditto for commercial galleries, which the fairs are mirroring.

Against these are not so many forces that I’m aware of, but — and I’m serious — the Burning Man phenomenon presents an alternative. This is a culture that is rooted in the notion of immediate experience and recognizes no academic limits.

I would not make a generalization that this west-coast phenomenon of large-scale, immersive works is necessarily better than more orthodox art, but the vitality is hard to dismiss, as is the sense of vision and the future, which is unabashedly on display. The blurring of lines between art and architecture, between artist and participant, between performance and spectatorship seems critical, if one wants to understand the most resonant art experiences to be had today.

Lastly: scale. Which seems more vital to the 21st century: a labyrinth of little galleries full of pictures and objects or a smaller number of grand productions, executed by far-flung, online-coordinated teams, that almost impossibly spring into life, to be experienced by the throng?